Navigate

Article List

- Editorial

By Albert Cheng, CEO, Singapore Bullion Market Association

- The Golden Future of Thailand’s Bullion Industry

By Pawan Nawawattanasub, CEO, YLG Bullion International

- LBMA/LPPM Conference: Gràcies Barcelona

By Shelly Ford, Digital Content Manager & Editor of the Alchemist, LBMA

- Central Bank Gold Buying Reaches Record Levels

By Shaokai Fan, Head of Asia-Pacific (ex-China) and Global Head of Central Banks, World Gold Council

- Why Platinum is a Strategically Important Metal

By Edward Sterck, Director of Research, the World Platinum Investment Council

- A Paradigm Shift in Japan’s Gold Market

By Bruce Ikemizu, Representative Director, Japan Bullion Market Association

- Gold’s Rush to the East

By Ronald-peter Stöferle, Managing Partner, Incrementum AG

- SBMA News

By SBMA

Article List

- Editorial

By Albert Cheng, CEO, Singapore Bullion Market Association

- The Golden Future of Thailand’s Bullion Industry

By Pawan Nawawattanasub, CEO, YLG Bullion International

- LBMA/LPPM Conference: Gràcies Barcelona

By Shelly Ford, Digital Content Manager & Editor of the Alchemist, LBMA

- Central Bank Gold Buying Reaches Record Levels

By Shaokai Fan, Head of Asia-Pacific (ex-China) and Global Head of Central Banks, World Gold Council

- Why Platinum is a Strategically Important Metal

By Edward Sterck, Director of Research, the World Platinum Investment Council

- A Paradigm Shift in Japan’s Gold Market

By Bruce Ikemizu, Representative Director, Japan Bullion Market Association

- Gold’s Rush to the East

By Ronald-peter Stöferle, Managing Partner, Incrementum AG

- SBMA News

By SBMA

Central Bank Gold Buying Reaches Record Levels

By Shaokai Fan, Head of Asia-Pacific (ex-China) and Global Head of Central Banks, World Gold Council

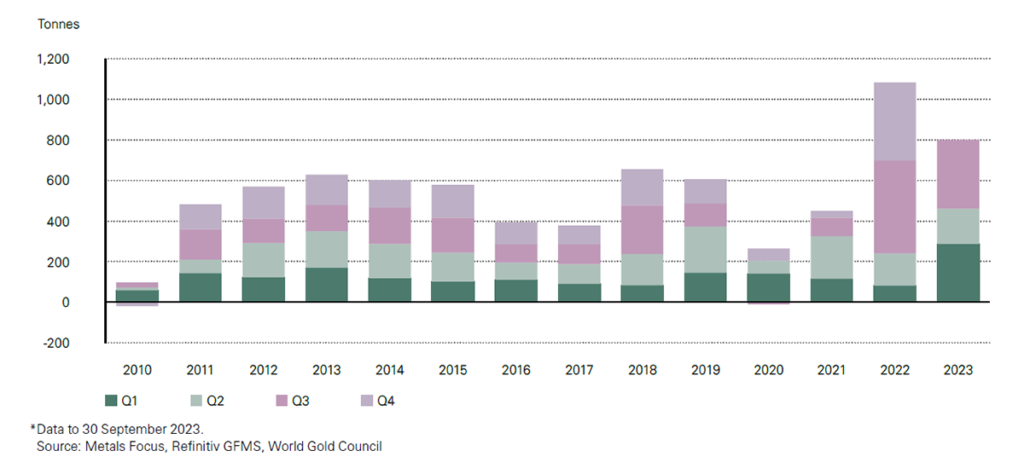

The past year has witnessed an unprecedented surge in central bank activity within the gold market. In 2022, the official sector added a remarkable 1,082 tonnes of gold, marking the largest annual net purchase in history. This was more than double the average annual gold purchases from central banks over the decade preceding 2022, which was roughly 512 tonnes per year. Last year marked a clear departure from the long-term trend, a phenomenon which has continued into 2023. During the first three quarters of this year, central banks added 800 tonnes of gold, an amount that far exceeds their full year in the previous decade, apart from the exceptional 2022.

Central bank demand has gone from strength to strength*

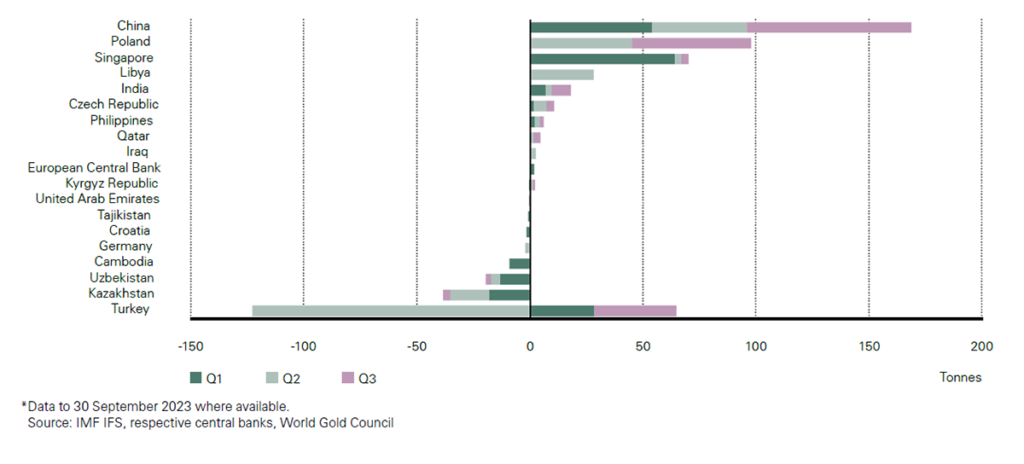

At the country level, the Chinese central bank emerged as the largest gold buyer in 2023, adding 155 tonnes to its reserves. The central banks of Poland and Singapore followed with 86 tonnes and 75 tonnes, respectively. One noteworthy change to the list of central bank gold buyers is Turkey’s shift to the selling column in 2023 with a 70-tonne reduction compared to a 148-tonne increase in 2022. Turkey’s abrupt change can be attributed primarily to the impact of its presidential election in early 2023. Ahead of the election, Turkish citizens snapped up gold and foreign currency to shield themselves from potential volatility in the Turkish lira. Combined with restrictions on gold imports, this situation led to extremely tight liquidity in the domestic gold market. In response, the Turkish central bank released gold from its reserves to alleviate the liquidity constraint, leading to a decline in its official gold holdings. With the election cycle now over, the Turkish central bank has resumed gold accumulation. Excluding the Turkish sales, central bank buying in 2023 would have been even more remarkable.

Why Are Central Banks Acquiring So Much Gold?

The extraordinary surge in central bank gold accumulation is not occurring in isolation. While each central bank has a reserve management strategy tailored to its unique circumstances, significant global trends may be prompting this large-scale shift towards gold. The global interest rate environment has been wrenched out of a decade-long quagmire of low or negative policy rates, as inflation rebounded following the lifting of Covid pandemic restrictions. Anaemic and uneven economic recoveries have also added uncertainty to the global macroeconomic outlook. These developments have reverberated across nearly every asset class, resulting in a drastic pullback in equities and rising bond yields. This uncertain landscape may be prompting some central banks to seek less correlated assets to mitigate overall portfolio risk. Gold’s idiosyncratic financial behaviour, which tends to perform well during times of market stress, likely factors into the considerations of central bank reserve managers.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 rekindled the once-distant possibility of two European nations engaging in armed conflict.

However, the most significant change may be the escalating great power rivalry, not only on the battlefield, but also in financial markets. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 rekindled the once-distant possibility of two European nations engaging in armed conflict. However, from a central banker’s perspective, the subsequent sanctions imposed on the Bank of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves were equally unsettling. While previous cases of central bank reserve asset freezes primarily revolved around disputes over governmental legitimacy and involved economically insignificant countries like Afghanistan or Iran, the sanctions against a major central bank with substantial foreign exchange reserves were unprecedented. This may have triggered an urgent reevaluation of the political risks associated with reserve assets. After all, what good is the most liquid financial instrument if it can be frozen at the discretion of a foreign power? Gold, as a physical financial asset, can be stored domestically and entirely shielded from external influence. While this might limit gold’s usability as a liquid instrument, it ensures immunity from freezing or confiscation. This factor is perhaps a key reason for the surge in central bank gold buying.

This year, unfortunately, has been no more stable than 2022. A devastating new conflict has erupted in the Middle East, threatening to engulf the region. China’s economy appears to be sputtering while political intrigue mounts, and US political stability was questioned as party infighting left a branch of Congress leaderless for weeks. A new term is starting to enter the vocabulary of investors and central bankers: “polycrisis”. The world appears to be moving towards greater disorder. Gold has demonstrated its resilience as a safe-haven asset during times of stress. It rallied during the Russian invasion of Ukraine and again following Hamas’ attacks on Israel. The gold price has remained relatively strong despite interest rates at multi-decade highs and a strong US dollar, both of which traditionally pose headwinds for gold. Central bankers may have turned to gold for the fundamental reality that the world has become more uncertain.

Reported purchases in 2023 dominated by China, Poland and Singapore*

Gold Producing Countries Are Increasingly Utilising Domestic Resources to Add to Reserves

It is important to note that while big economies are snapping up large amounts of gold, another class of central banks has also become more active in this space as well – emerging market central banks from countries that produce gold domestically, particularly small-scale artisanal gold mining (ASGM). This is not an entirely new phenomenon. The central bank of the Philippines has operated a domestic gold buying programme for several decades now. However, in recent years, we have seen a proliferation of this trend in Africa and Latin America. The central banks of Tanzania, Mongolia, and Ecuador all have active ASGM buying programmes and have accumulated gold reserves as a result.

The benefits for central banks are straightforward. They can acquire a reserve asset with their domestic currency without relying on international trade. They can also source gold without having to exchange it for another international currency. For local ASGM producers, having the central bank as an off-taker can ensure a reputable, transparent, and trustworthy buyer. The central bank can leverage its market position to compel ASGM producers to comply with international standards for environment, social, and governance practices. Although the scale of gold reserve accumulation from these programmes may not be massive, the ability for central banks to utilise domestically mined gold provides a powerful tool to shore up their reserves, bolster financial stability, and boost investor confidence. It also helps to ensure that ASGM production in these countries becomes formalized, transparent, and compliant with international standards. This phenomenon is a significant aspect of the central bank gold story.

Outlook for Central Bank Gold Purchases

The extraordinary levels of central bank gold buying have persisted into 2022, defying our initial expectations. Central banks are now entering their fourteenth consecutive year of net gold accumulation, marking a remarkable departure from the decades of net selling in the 1980s and 1990s. The question of whether this buying spree will continue at the same pace is remains uncertain. Despite the recent gold binge, the metal still represents only around 5% of the reserves of emerging market central banks. A sudden reversal of total reserve levels – triggered by efforts to combat currency instability resulting from a financial shock or a pandemic, for instance – could hinder the ability of central banks to continue acquiring gold. However, with prolonged conflicts in multiple regions, growing political instability, and mounting pressure from great power rivalries, the world is looking like it will continue its slow slide into further disarray. Central banks would be wise to continue seeking assets that can withstand this uncertain environment.

SHAOKAI FAN is the Head of Asia-Pacific (exChina) and Global Head of Central Banks at the World Gold Council. He advises governments on gold matters and engages with central banks and sovereign wealth funds on investment considerations. Shaokai previously worked at Standard Chartered Bank in various roles. He holds a Master’s degree in Public Administration from Columbia University and the London School of Economics, and an undergraduate degree in finance and economics from New York University.