Navigate

Article List

- SBMA News

By SBMA

- Safe Haven Meets Safe Harbour

By Terry Hanlon, President and CEO, Dillon Gage Metals

- Gold in 2023: Factors Influencing its Performance

By Nicholas Frappell, Global Head Institutional Markets, ABC Refinery

- The Recovery of Thai Gold Demand and its Saving Scheme

By Pawan Nawawattanasub, CEO, YLG Bullion Singapore

- Gold to Shine Again

By Chen Guangzhi, Head of Research, KGI Securities (Singapore)

- The One Bank for ASEAN: Shaping the Gold Landscape from Singapore to China and Beyond

By United Overseas Bank

- The Evolution of Central Bank Gold Buying: Reasons Behind 2022’s Record-Breaking Purchases

By Shaokai Fan, Head of Asia-Pacific (ex-China) and Global Head of Central Banks, World Gold Council

- Metalor Technologies’ Commitment to Responsible Sourcing in Precious Metals Industry

By Jonathan J. Jodry, Business Development Director, Metalor Technologies

- Tokenisation Carries more than its Weight in Gold when it comes to ESG

By Anouska Rayner, Head of Growth Commodities, Paxos

- Using Gold ETFs as a Store of Value

By Geoff Howie, Market Strategist, Singapore Exchange Limited

- The Fed’s Dual Mandate, Strong Physical Markets a Mana for Gold

By Bart Melek, Managing Director & Global Head of Commodity Strategy, TD Securitie

Article List

- SBMA News

By SBMA

- Safe Haven Meets Safe Harbour

By Terry Hanlon, President and CEO, Dillon Gage Metals

- Gold in 2023: Factors Influencing its Performance

By Nicholas Frappell, Global Head Institutional Markets, ABC Refinery

- The Recovery of Thai Gold Demand and its Saving Scheme

By Pawan Nawawattanasub, CEO, YLG Bullion Singapore

- Gold to Shine Again

By Chen Guangzhi, Head of Research, KGI Securities (Singapore)

- The One Bank for ASEAN: Shaping the Gold Landscape from Singapore to China and Beyond

By United Overseas Bank

- The Evolution of Central Bank Gold Buying: Reasons Behind 2022’s Record-Breaking Purchases

By Shaokai Fan, Head of Asia-Pacific (ex-China) and Global Head of Central Banks, World Gold Council

- Metalor Technologies’ Commitment to Responsible Sourcing in Precious Metals Industry

By Jonathan J. Jodry, Business Development Director, Metalor Technologies

- Tokenisation Carries more than its Weight in Gold when it comes to ESG

By Anouska Rayner, Head of Growth Commodities, Paxos

- Using Gold ETFs as a Store of Value

By Geoff Howie, Market Strategist, Singapore Exchange Limited

- The Fed’s Dual Mandate, Strong Physical Markets a Mana for Gold

By Bart Melek, Managing Director & Global Head of Commodity Strategy, TD Securitie

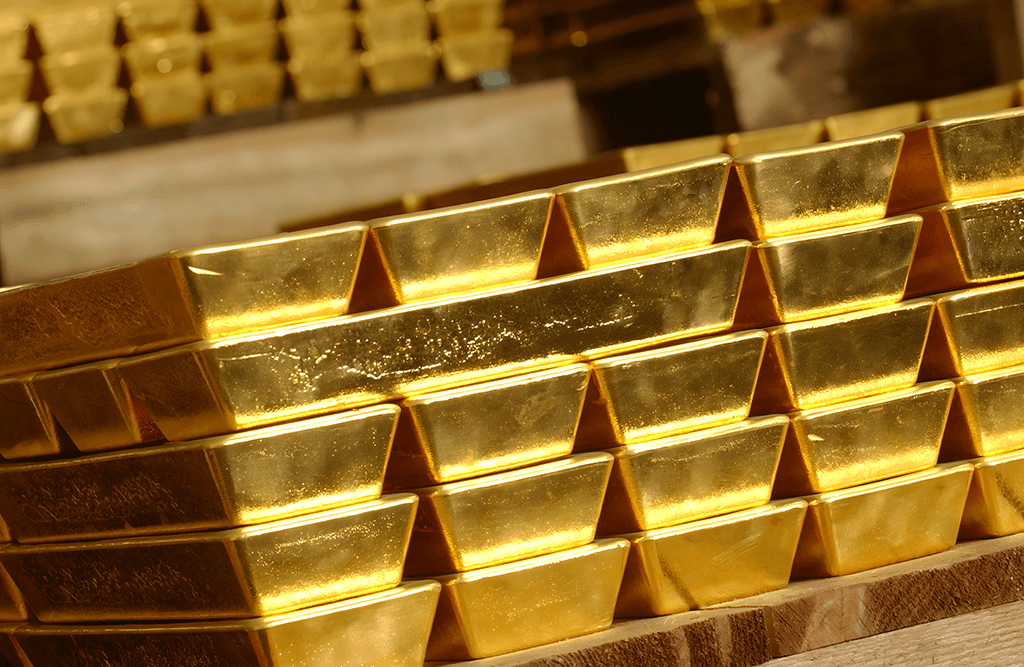

The Evolution of Central Bank Gold Buying: Reasons Behind 2022’s Record-Breaking Purchases

By Shaokai Fan, Head of Asia-Pacific (ex-China) and Global Head of Central Banks, World Gold Council

In 2022, central banks bought a record-breaking amount of gold, adding over 1,100 tonnes of the yellow metal. While the war in Ukraine and rampant inflation may have played a role, some might think that it is only natural for central banks, alongside many other investors, to load up on gold.

While these factors may have figured in the minds of central bankers, the evolution of their thinking towards holding gold has shown considerable evolution in the past two decades. While 2022 may have been an historically strong year for central bank gold buying, it is but the latest in a thirteen-year stretch of net buying by these institutions.

A Slow Evolution from Net Sellers to Net Buyers

Central banks have long been familiar with gold as an asset class. Through variations of historical gold standards, central banks accumulated large gold reserves initially to back their paper currencies. After the end of the Second World War, the implementation of the Bretton Woods system continued to place gold at the heart of the international monetary system. The US dollar would be pegged to gold with guaranteed convertibility at a fixed rate, while all other currencies would be pegged to the US dollar. However, skyrocketing US budget deficits in subsequent decades led to a breakdown of the Bretton Woods system until the US finally suspended the convertibility of the dollar to gold in 1971, effectively ending gold’s formal role in the international monetary system.

For several decades after the end of the Bretton Woods system, central banks found themselves managing large gold reserves despite the fact that it no longer had any formal function in backing currency. This led to a sustained period of central bank gold sales, in particular from Western European central banks. For many years, central banks were net sellers of gold and it seemed like the yellow metal would never regain its once-prominent role as an international reserve asset. The 2008 global financial crisis abruptly reversed this phenomenon, however, as the advent of quantitative easing by many central banks sparked fears of currency debasement and the spectre of hyperinflation. Western European central banks ended their gold sales as they found value in gold as a strategic asset amid a quickly changing monetary environment. More significantly however, emerging market central banks began to accumulate large quantities of gold reserves as they saw their large US dollar holdings come under threat from quantitative easing.

Three Phenomena Driving Central Bank Gold Buying Post-2008

In the years since the 2008 global financial crisis, central banks’ attitude towards gold has been defined by several major phenomena: Western central banks have ended gold sales but are unlikely to add additional gold, emerging market central banks have emerged as the driving force behind new gold buying, and central banks in countries that produce gold have developed programmes to add gold reserves through domestic production. Among these, the buying from emerging markets has largely reshaped the story of gold as a central bank reserve asset.

Since 2008, the central banks of Russia, China, India, Turkey, and many other larger emerging market economies have added significant quantities of gold to their reserves. Furthermore, many other emerging markets central banks including those of Thailand, Brazil, Hungary, and Poland, have also made notable purchases. These central banks started with a very low level of gold holding compared to their advanced economy peers. The drive to diversify their reserve assets from a variety of risks, ranging from market-driven factors to purely political risks, has naturally led many of them to choose gold.

In addition, the central banks of countries like Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Mongolia, and others have tapped domestic gold production to add to their official reserves. This method can be tremendously advantageous as it allows a central bank to pay for a reserve asset using local currency, whereas buying gold on the international market would require exchanging a hard currency (like the US dollar) for gold. In recent years, this facet of central bank gold buying has spread to several other countries. The central banks of Zambia, Tanzania, Ecuador, and others have started or restarted domestic gold buying programmes.

Why Central Bank Gold Buying Broke Records in 2022

Returning to the record-breaking level of central bank gold buying in 2022, there are several factors that may have driven this extraordinary amount of activity. Global geopolitical stability has been markedly less certain, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has refocused attention on other global hotspots like the Taiwan Straits or the Korean peninsula. Strong Western unity against the invasion has strengthened ties between Russia and China, while many non-aligned countries are precariously balancing relations between these two camps. This has prompted a wave of de-globalisation and heightened tensions.

From a central bank perspective, the rapid imposition of sanctions against the Russian central bank’s foreign currency reserves was a new and unexpected response. While some central banks have faced sanctions before, none approached the size and importance of the Bank of Russia. The freezing of its offshore foreign currency reserves proved that the US dollar could indeed be weaponised at a large scale. While most central banks do not anticipate a hostile showdown with the West, the sanctions against the Russian central bank may have prompted a rethinking of the nature of political risk and the accessibility of a central bank’s foreign currency reserves that are domiciled overseas.

Gold, if stored domestically, is immune from seizure. While a country facing international sanctions would have difficulty using gold for cross-border transactions, its mere existence provides a level of comfort within a domestic economy and financial markets. This may have been a factor that has prompted the large-scale gold buying in 2022. For the first time in several years, China’s central bank reported gold purchases, for instance. Furthermore, large gold purchases also came from the central banks of Iraq, Egypt, Turkey, and the UAE in 2022 as well.

Singapore Joins Gold Buying Trend

Singapore has not been a bystander in the recent rush to gold among central banks. In January and February 2023, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) reported a 51-tonne increase in its gold reserves. Despite the impressive purchase, this action only brought gold to roughly 2% of the MAS’ total official reserves due to the vast size of Singapore’s war chest. It also marked the second time in recent history that the MAS bought gold, complementing a roughly 40-tonne purchase in 2021. These purchases were the first time that the MAS added gold in decades.

The MAS is characteristically tight-lipped about its rationale for adding gold. However, these purchases coincide with an increasing drumbeat of concerns about the state of regional geopolitics from Singapore’s political leaders. The fallout from the war in Ukraine has reignited old fears of conflict in East Asia, in which Singapore would undoubtedly be affected. Those fears, combined with the MAS’ relative low level of gold holdings, may have prompted a renewed interest in gold. However, as with many central banks, the rationale will be closely held by the decision-makers.

Will Central Banks Continue to Buy Gold?

Central bank investment trends can be difficult to assess. Their investment decisions are not purely based on market factors but usually involve elements of political and strategic calculation as well. Therefore, it is difficult to say whether central bank gold buying will continue, and certainly whether it will continue at the blistering pace we witnessed in 2022. However, the first quarter of 2023 has so far shown a continuation of the trends seen last year. China continued to report gold buying in the first quarter while the aforementioned purchases from Singapore also confirms the ongoing interest in buying.

The fundamental reasons that drove central bank gold buying last year continue to persist. In fact, recent discussions have increasingly focused on the long-term role of the US dollar in the global economy and whether alternative currencies or arrangements should displace its supremacy. China has been playing a more active role in the Middle East, and more oil is now being denominated in renminbi than before. The BRICs countries have also floated the idea of an alternative currency system. Most analysts predict that the US dollar will continue to be the unparalleled currency of international trade for many years to come, but its position will face a steady erosion that may be accelerated due to the weaponisation of the dollar in recent years.

What this may mean for gold as a reserve asset is still unclear. However, the central bank of Hungary may have provided some insights into how central banks view this phenomenon. After a substantial gold purchase in 2019, the Magyar Nemzeti Bank issued a press release detailing its rationale, a rare step by a central bank. The press release stated that the Hungarian central bank added gold because it foresees disruption during a period of transition in the international monetary system, and that gold has traditionally been a risk mitigator during such periods. With so much uncertainty clouding the global outlook at this stage, perhaps gold can still shine as a beacon of stability.

SHAOKAI FAN is the Head of Asia-Pacific (ex-China) and Global Head of Central Banks at the World Gold Council. He advises governments on gold matters and engages with central banks and sovereign wealth funds on investment considerations. Shaokai previously worked at Standard Chartered Bank in various roles. He holds a Master’s degree in Public Administration from Columbia University and the London School of Economics, and an undergraduate degree in finance and economics from New York University.