Navigate

Article List

- Editorial

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

- The Effects of Covid-19 on Australia’s Precious Metals Market

By Bron Suchecki, Senior Precious Metals Project Analyst, Pallion

- Will Covid-19 Slow Gold Production in Russia?

By Sergey Kashuba, Chairman, Union of Gold Producers of Russia

- Consumer Behaviour Towards Gold Jewellery in Indonesia

By Jennifer Heryanto, Chief Executive Officer, SKK Jewels

- Korea’s Gold & Jewellery Market

By Da Young Kim, Senior Researcher, Wolgok Jewelry Research Center

- Feature | Gold Rush 2.0: Australia to Become World’s Biggest Gold Producer

By Shae Russell, Chief Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia

- Special Focus | Japan Bullion Market Association

By Bruce Ikemizu, Chief Director, Japan Bullion Market Association

- Global Overview of Precious Metal Logistics

By Allan Finn, Director of Global Commodities, Malca-Amit

- Gold Demand Trends and The Impact of Covid-19

By Andrew Naylor, Head of ASEAN and Public Policy, World Gold Council

- Road Toward $2,000+ Gold Set to Be a Bumpy One

By Bart Melek, Global Head of Commodity Strategy, TD Securities

- SBMA News

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

Article List

- Editorial

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

- The Effects of Covid-19 on Australia’s Precious Metals Market

By Bron Suchecki, Senior Precious Metals Project Analyst, Pallion

- Will Covid-19 Slow Gold Production in Russia?

By Sergey Kashuba, Chairman, Union of Gold Producers of Russia

- Consumer Behaviour Towards Gold Jewellery in Indonesia

By Jennifer Heryanto, Chief Executive Officer, SKK Jewels

- Korea’s Gold & Jewellery Market

By Da Young Kim, Senior Researcher, Wolgok Jewelry Research Center

- Feature | Gold Rush 2.0: Australia to Become World’s Biggest Gold Producer

By Shae Russell, Chief Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia

- Special Focus | Japan Bullion Market Association

By Bruce Ikemizu, Chief Director, Japan Bullion Market Association

- Global Overview of Precious Metal Logistics

By Allan Finn, Director of Global Commodities, Malca-Amit

- Gold Demand Trends and The Impact of Covid-19

By Andrew Naylor, Head of ASEAN and Public Policy, World Gold Council

- Road Toward $2,000+ Gold Set to Be a Bumpy One

By Bart Melek, Global Head of Commodity Strategy, TD Securities

- SBMA News

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

Feature: Gold Rush 2.0: Australia to Become World’s Biggest Gold Producer

By Shae Russell, Chief Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia

Published on June 10, 2020

SHAE RUSSELL is the chief editor of The Daily Reckoning Australia, where she breaks down global macro-economic trends for Australians, and is Fat Tail Media’s leading analyst on bullion and precious metal miners.

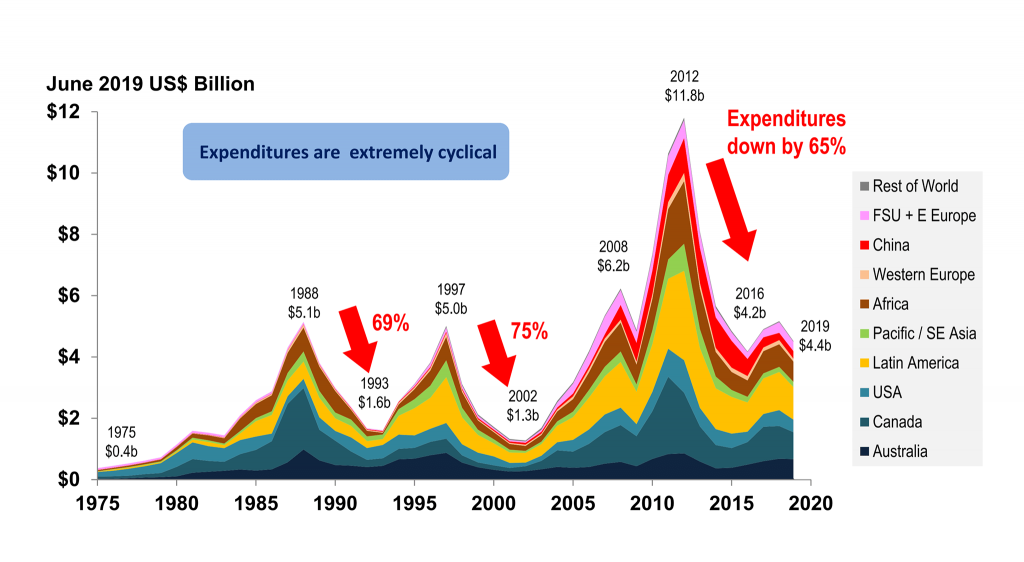

The price of gold is starting to stretch its legs. But years of underinvestment in both exploration and mine expansion mean that many miners around the world are at risk of having little left to dig up. When the gold price falls, exploration is the first thing to go from the budget. Yet it can take a decade or more to turn a gold find into a gold mine.

Rising prices mean we’re prepared to pay top dollar for precious metals. But globally, gold miners didn’t build their resources when the price was low. By underinvesting in exploration, they’ve hurt future production and are missing out on a once-a-century opportunity.

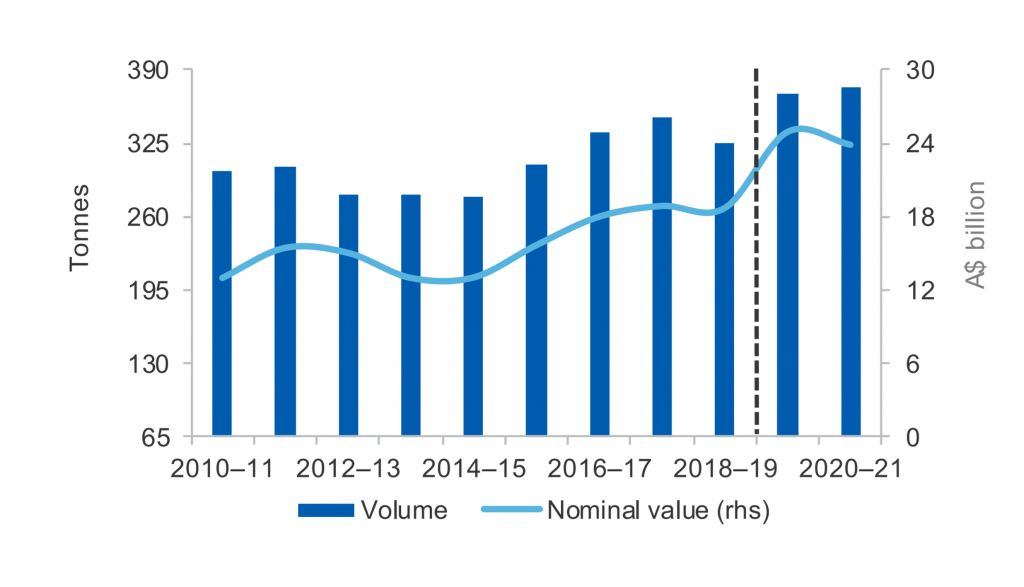

Next year, Australia will be the world’s largest gold producer, producing an estimated 383 tonnes of gold, and will knock China off the top spot it’s held since 2007.1

One estimate for the Middle Kingdom says that growth will be stagnant over the next decade, suggesting that Russia will overtake the country and bump it all the way down to number three.

Australia didn’t become number one by accident though. Currency parity with the US dollar back in 2010–11 meant some gold miners were losing money. This brief moment, when one Aussie dollar was worth more than one greenback, forced Australian gold miners to become lean producers. Not only did Aussie gold miners cut the bloat from the budget, they streamlined processes to produce more gold for less cost.

ONE OF THE UNIQUE FEATURES OF THE AUSTRALIA’S GOLD MINING INDUSTRY IS THAT EVERY SINGLE STATE HAS GOLD RESERVES AND IS ACTIVELY MINING GOLD.

Australia’s gold exports, 2010–20

GOLD-RICH

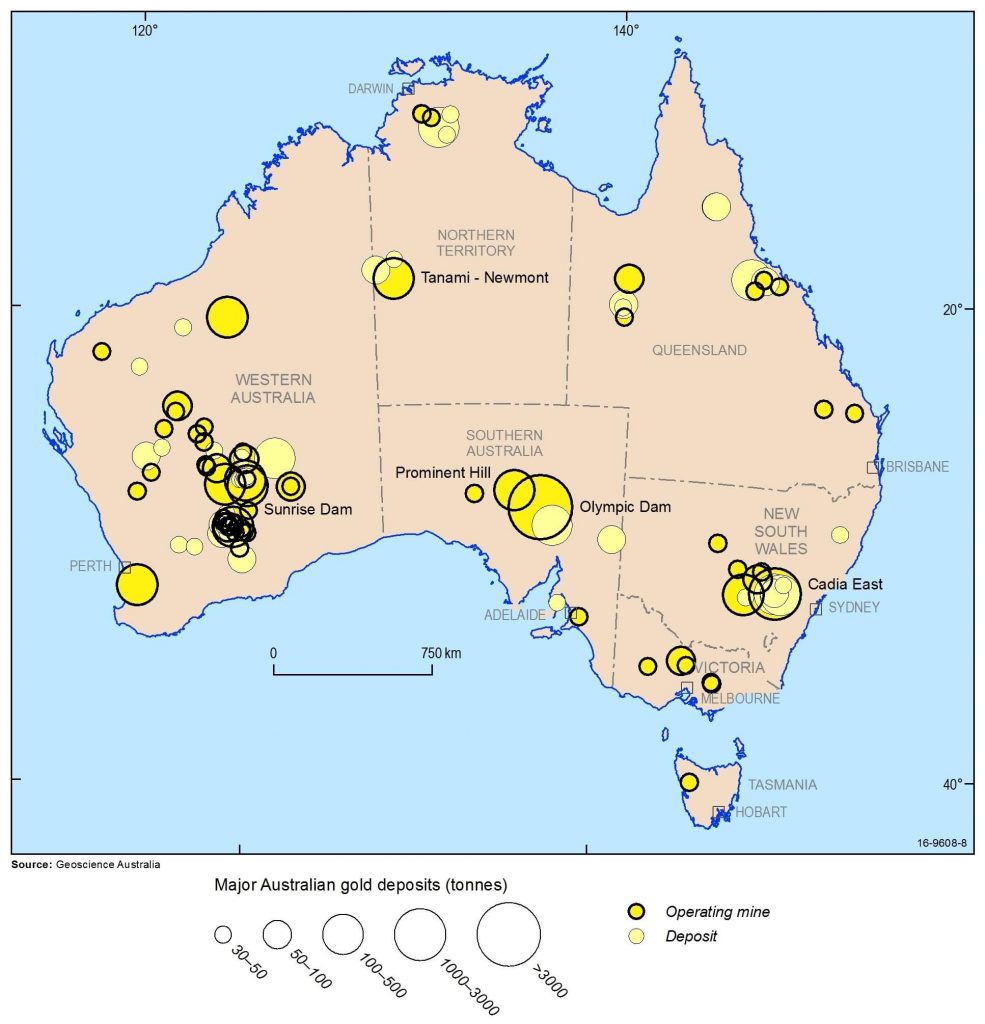

Australia’s 17% of economically demonstrated resources (EDR) is 5.6 times higher than China’s 3%. In fact, Australia’s gold reserves are larger than in Russia or South Africa. Australia’s known gold deposits are even larger than the US and Canada’s reserves combined.

The stories of how gold mining emerged in Australia pretty much involves stumbling upon the shiny rock: a nugget was found in a riverbed in a place called Poverty Point. Once word of this nugget spread, the 1850s gold rush began. On the west coast in the 1890s, a horse kicked over a rock and gold was found. This very spot went on to house Australia’s longest running gold mine, pouring gold for 120 years.

The ease of finding gold has much to do with Australia hitting the geological jackpot. We are literally peppered with gold deposits. Some places have richer gold plots than others. One of the unique features of the Australia’s gold mining industry is that every single state has gold reserves and is actively mining gold.

Western Australia has about 43% of economically demonstrated resources (EDR), yet this state produces a mammoth 70% of the country’s total gold. While Western Australian is famous for its Super Pit (a joint venture between Saracen Holdings and Northern Star), it is only Australia’s second biggest producer of gold.

Top spot goes to Boddington (Newmont Corp), which is located 120 kilometres from Perth and pours a whopping 741,000 ounces of gold per year on average. Newmont Corp owns another big gold producer in in the Northern Territory (4% of EDR) – the Tanami mine, which produces 500,000 ounces annually.

Major gold deposits in Australia

However the biggest gold miner by ounces is the copper gold porphyry Cadia mine operated by Newcrest Mining in New South Wales (18% of EDR), which sent some 871,216 ounces to market last year. Newcrest is out to make Cadia an even bigger miner, increasing production from less than 28 tonnes (900,000 troy ounces) of gold in 2019, to a mammoth 35 tonnes (1,125,000 ounces of gold) of gold by 2023.

Head a little further south and you’ll find one of the richest gold mines in the world.

The Fosterville mine (Kirkland Lake Gold) is the largest gold producer in Victoria (1% of EDR), pouring 619,366 ounces in 2019. While it doesn’t produce as much as others, the transformation at Fosterville is reviving the Victorian gold mining industry.

Fosterville is smack in the guts of the first Australian gold rush. By simply digging deeper, Fosterville has become one of the highest gold grade mines in the world, with an average grade of 39.6 grams per tonne.

EXPLORATION CRUCIAL FOR SUCCESS

Mining is an odd business. Your greatest asset is a depleting one. An ounce out of the ground is an ounce out of the ground. In spite of how important it is to secure a future resource, exploration is the first thing to go when the price of gold dives.

SUCCESSFUL EXPLORATION TODAY MEANS INCREASED GOLD PRODUCTION A DECADE FROM NOW.

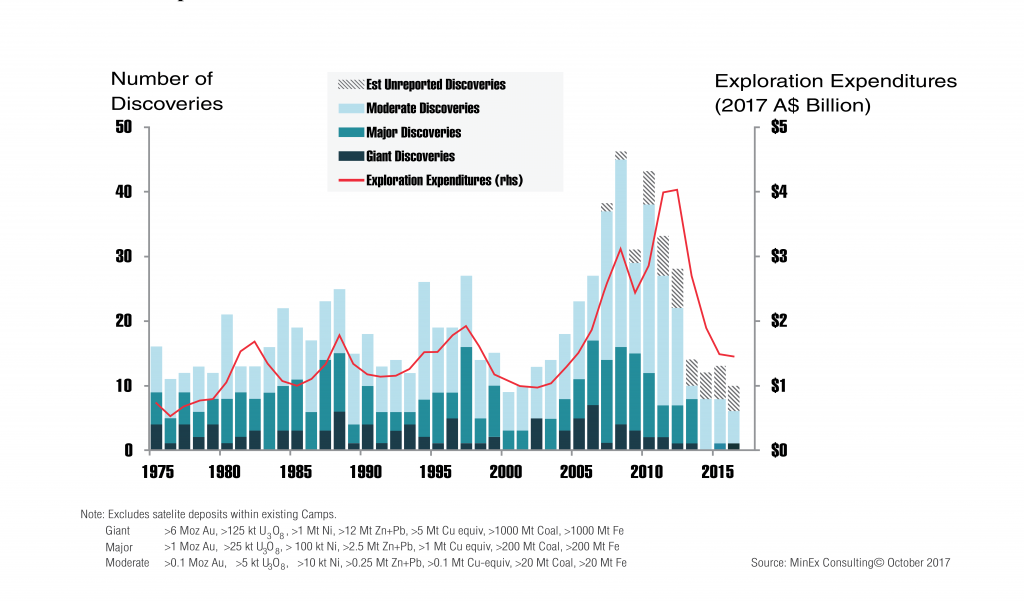

Global exploration expenditures peaked when the gold price hit an all-time high, as the price fell so did the money spent looking for it. This short-sighted thinking from miners hinders future production. Successful exploration today means increased gold production a decade from now.

Aussie miners are in an enviable position right now. The weakening Aussie dollar is pushing the Aussie dollar gold price up. Higher prices not only encourage increased production, but creates an incentive to spend big and go looking for more.

As it stands, Australia is one few gold producers with exploration spending back to 2012 levels. Nevertheless, it has to be this way as gold is becoming increasingly harder to find.

The last tier 1 or giant discovery in Australia was the Tropicana deposit in 2005. However, Australia isn’t alone – giant discoveries of almost any commodity are almost non-existent. There are two reasons for this: lack of spending on exploration and having to look harder. The easy gold at the surface has been found.

Australia, and many other gold producing nations, must spend more money than ever before to find gold. To ensure efficiency, exploration programs will need to be carefully targeted. “Nearology” may be successful for existing mines. Yet greenfield sites will need extensive geophysics before any drilling can begin.

This will be expensive, but once again luck strikes Australia. Here the average depth from surface for a discovery is quite low. The average depth for a brownfield site in the Lucky Country is just 299 metres, compared to the US, where it is 415 metres.

THERE HAS BEEN A PERSISTENT UNDERINVESTMENT AND MISINVESTMENT IN GOLD EXPLORATION AROUND THE WORLD.

Global gold exploration expenditures 1975–2020

Global outlook: Number of discoveries correlate with exploration spending

It is a similar story for greenfield sites. A new find in Australia is on average only 30 metres from the surface and in the US the average greenfield site begins another 10 metres on top of that.2

High gold prices encourage deeper exploration, but perhaps this isn’t the answer to securing more gold. Technology advances can drastically alter commercial viability of a mine. The next giant discovery may not come from exploration, rather a change in what’s an economical project.

Carbon in pulp processing was a revolution for American gold miners in the 1970s, and as a result was commonplace in Australian mining by the 1980s. This was a game-changer for the industry. Low gold grade deposits could now be processed. This technology not only transformed what could be mined, it set Australia up to become the dominant supplier of gold it is today.3

There has been a persistent underinvestment and misinvestment in gold exploration around the world. Australia has been well prospected, but not well explored. Higher gold prices and technology advancement could see Aussie gold miners prosper well into the 2020s.

Notes

SHAE RUSSELL is the chief editor of The Daily Reckoning Australia, where she breaks down global macro-economic trends for Australians, and is Fat Tail Media’s leading analyst on bullion and precious metal miners.

* This article was published in partnership with The Daily Reckoning Australia