Navigate

Article List

- SBMA Successfully Concludes First Virtual APPMC

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

- APPMC: Market Updates

By SBMA

- The Significance of SPDR Gold Shares Dual Currency Trading

By Geoff Howie, Market Strategist, Singapore Exchange

- Our Vision for the Gold Market

By Andrew Naylor, Head of ASEAN and Public Policy, World Gold Council

- The New Investment Landscape is Green

By Vikas Shenoy, Head of APAC Origination & Partnerships, Trovio

- Gaining Exposure to Gold via Streaming and Royalty Companies

By Emil Kalinowski, Researcher, Wheaton Precious Metals

- There is Still Mettle Left in the Precious Metals

By Bart Melek, Global Head of Commodity Strategy, TD Securities

- SBMA News

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

Article List

- SBMA Successfully Concludes First Virtual APPMC

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

- APPMC: Market Updates

By SBMA

- The Significance of SPDR Gold Shares Dual Currency Trading

By Geoff Howie, Market Strategist, Singapore Exchange

- Our Vision for the Gold Market

By Andrew Naylor, Head of ASEAN and Public Policy, World Gold Council

- The New Investment Landscape is Green

By Vikas Shenoy, Head of APAC Origination & Partnerships, Trovio

- Gaining Exposure to Gold via Streaming and Royalty Companies

By Emil Kalinowski, Researcher, Wheaton Precious Metals

- There is Still Mettle Left in the Precious Metals

By Bart Melek, Global Head of Commodity Strategy, TD Securities

- SBMA News

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

Gaining Exposure to Gold via Streaming and Royalty Companies

By Emil Kalinowski, Researcher, Wheaton Precious Metals

Published on June 10, 2021

EMIL KALINOWSKI joined Wheaton Precious Metals in 2014. His research focuses on how socioeconomic and geopolitical trends affect the supply, demand, and price of precious and base metals. His present focus is on the malfunction of the monetary system in 2007 and how its continuing disorder has impacted commodity prices, macroeconomic trends and long-term country risks. He is also a part-time radio talk show hosts a YouTube channel on economic and finance. He previously held positions at State Street and Goldman Sachs.

The casual precious metal investor will likely consider only one of three categories of ownership: physical bullion, a metal-backed exchange-traded product (ETP), or equity in a metal producer. But for the well-versed investor, there is another category to investigate: streaming and royalty companies.

The streaming and royalty business has been in existence just as long as metal-backed ETPs. Indeed mere days separate their introduction to global markets. In October 2004, the first streaming company, Wheaton Precious Metals, began trading on the Toronto Stock Exchange. A month later, State Street, with the World Gold Council’s sponsorship, brought the SPDR Gold Trust to the market.

In only the loosest sense can it be described as a “sibling rivalry” because Wheaton was stuck in the shadow of the towering, immediate success of the ETP. Not only did the SPDR Gold Trust spawn aureate imitators across the world, but argent replicators (i.e. iShares Silver Trust). The product would become the world’s second-most valued ETP behind the SPDR S&P 500, but even briefly, the very biggest.

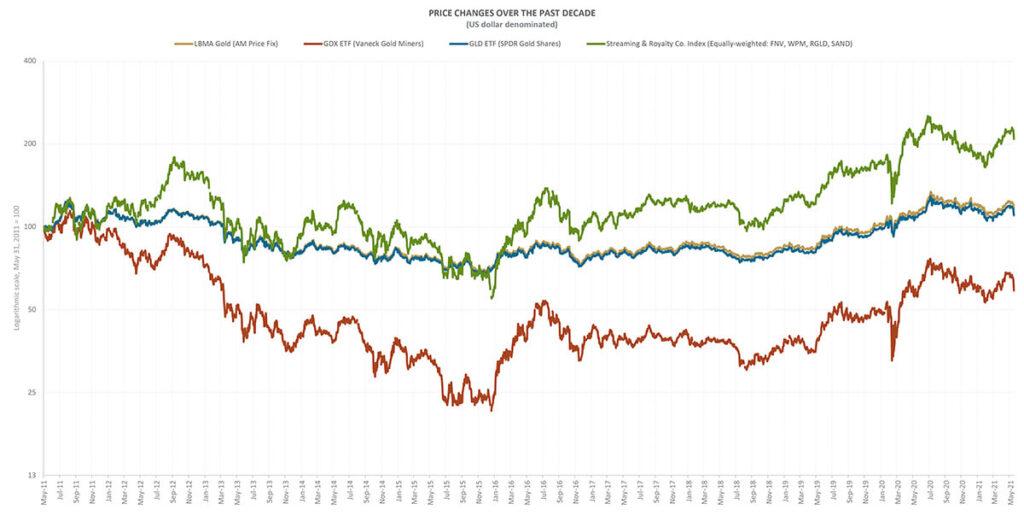

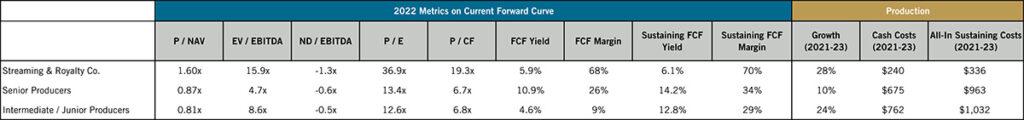

However, in recent years their roles have reversed, the just-as-successful performance of the streaming and royalty company is underappreciated. This precious metals investment category has risk-return characteristics that are entirely appealing, with more upside than an ETP but less risk than the equity shares of a metal producer.

STREAMING COMPANY

WStreaming companies (Stream Co.) work by making an upfront payment to the mining company (Mine Co.) for a portion of metal produced. Stream Co. will also make additional payments upon delivery of the metal. The additional payments to Mine Co. are predetermined at the time of the contract and are either fixed (e.g. $800 per gold ounce) or based on a proportion of the metal price (e.g. 20% of palladium’s spot market price).

Why would Mine Co. give up any of its hard-earned metal? The upfront payment can help fund exploration, a greenfield development and/or a brownfield expansion. Alternatively, the upfront payment can have nothing to do with the field but instead be leveraged at the company’s headquarters: repairing Mine Co.’s balance sheet and/or funding a merger or acquisition.

But most importantly, Mine Co. may be enticed to part with its hard-earned metal because the metal being streamed is not the core business. How can this be? Mother Nature’s preference is to create polymetallic deposits, consequently the copper mine produces copper but also: gold, molybdenum, silver, rhenium, zinc, etc.

Copper Mine Co. is in the copper business and capital markets will both fund and value the enterprise on its copper business, not its byproducts. If Copper Mine Co. is at peace with this market evaluation it will treat its byproducts as credits to the cost of the copper operation, or as incidental revenue.

Alternatively, it can bundle up years of anticipated byproduct production and exchange the bundle for an upfront payment (and payments-on-delivery), and employ the capital immediately.

On the whole, 16 years of evidence suggests that metal producers do not believe capital markets value their byproduct appropriately. According to Sandstorm Gold, a major streaming and royalty company, the sector struck US$23.4 billion worth of agreements between 2010 and 2019, with 74% of dollars structured as streaming contracts.

ROYALTY COMPANY

A royalty company (Royalty Co.) has many similarities to streaming companies. Royalty Co., likewise, makes an upfront payment to Mine Co. but instead of receiving a percentage of metal, it receives a share of revenues.

Other differences include Royalty Co. not making additional payments to Mine Co. (existing exceptions prove the rule). Also, Royalty Co. partnerships are typically with a Gold Mine Co. or a Silver Mine Co., as it seeks exposure to precious metals directly instead of via byproducts.

There are different royalty “flavours” within the two main groups: revenue-based and profit-based. The former is top-line and can come “gross” or “net smelter” (i.e. after the smelter gets paid). The latter is bottom-line and is paid out after capital costs or operating and capital costs. Franco-Nevada, a major streaming and royalty company, estimates that royalties are typically in the range of 1% to 5%.

STREAMING AND ROYALTY COMPANIES

The streaming and royalty sector increased gold production by 6% year-on-year in 2019. Its proportion of global gold mine supply remained unchanged in 2019, at 1%. The sector decreased silver production by 5% in 2019 relative to the year previous. Its proportion of global silver mine supply fell in 2019 to 4.3% from 4.5% in 2018.

If all companies are rescaled to gold-equivalent ounces, the industry saw a 2.6% decrease in production for 2020, according to Canaccord Genuity Capital Markets. The industry is forecast to expand by 17% by 2022. Looking further out, BMO Capital Markets sees gold-equivalent ounces rising by 33% by 2025 relative to 2020’s low.

According to Metals Focus, in 2019 the five largest precious metal streaming and royalty companies – Franco-Nevada, Osisko Gold Royalties, Royal Gold, Sandstorm Gold, Wheaton Precious Metals – accounted for 98% of the gold subject to streaming and royalty agreements. However, there are many more names to consider.

EMIL KALINOWSKI joined Wheaton Precious Metals in 2014. His research focuses on how socioeconomic and geopolitical trends affect the supply, demand, and price of precious and base metals. His present focus is on the malfunction of the monetary system in 2007 and how its continuing disorder has impacted commodity prices, macroeconomic trends and long-term country risks. He is also a part-time radio talk show hosts a YouTube channel on economic and finance. He previously held positions at State Street and Goldman Sachs.