Navigate

Article List

- The Future Of India’s Gold Industry

By Neelambari Dasgupta & Srivatsava Ganapathy, Bullion Bulletin

- The Gold Market: How History Has Shaped The Present

By Rhona O’Connell, Head of Market Analysis, EMEA and Asia, INTL FCStone

- Europe’s Renewed Interest In Gold

By Ronald Stoeferle, Managing Partner, Incrementum AG

- SBMA News

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

Article List

- The Future Of India’s Gold Industry

By Neelambari Dasgupta & Srivatsava Ganapathy, Bullion Bulletin

- The Gold Market: How History Has Shaped The Present

By Rhona O’Connell, Head of Market Analysis, EMEA and Asia, INTL FCStone

- Europe’s Renewed Interest In Gold

By Ronald Stoeferle, Managing Partner, Incrementum AG

- SBMA News

By Albert Cheng, CEO, SBMA

Europe’s Renewed Interest in Gold

By Ronald Stoeferle, Managing Partner, Incrementum AG

Published on December 20, 2019

In Europe, institutional and individual investors alike are showing renewed interest in gold. The reasons for this trend are manifold: negative interest rates, the set-back of equity markets in Q4/2018, slowing economic growth, and a growing distrust in the sustainability of the global political and economic order and the stability of financial markets.

Until the Great Financial Crisis of 2007/2008, central banks were net sellers of gold. Gold was considered a “barbarous relic”, a non-interest bearing reserve that should be substituted for interest-bearing assets. This view has changed since then. In particular, the so called axis of gold – a term coined by investor and economist Jim Rickards to refer to Russia, China, Iran and Turkey – have significantly increased their gold reserves in the last decade. In 2018, central banks of EU countries joined the group of gold advocates and buyers.

With regards to gold’s role in central bank reserves, two recent statements by European central banks merit closer scrutiny. When the Central Bank of Hungary (MNB) conducted its first gold purchases since 1986 last year, increasing its gold reserves tenfold, it published the following statement:

In normal circumstances, gold has a confidence-building feature, i.e. it may play a stabilising role and act as a major line of defence under extreme market conditions or in times of structural changes in the international financial system or deep geopolitical crises. In addition, gold continues to be one of the safest assets, which can be related to individual properties such as the limited supply of physical precious metal, which is not linked with credit or counterparty risk, given that gold is not a claim on a specific counterparty or country.1

Central banks are known for their balanced communication, as they want to avoid any overreaction by the public, which may have severe economic and financial consequences. Against this background, MNB’s frankness is as surprising as telling. Yet, although a member of the European Union since 2004, Hungary has not joined the eurozone and will not join it anytime soon. MNB governor Gyorgy Matolcsy even called the euro a “strategic error” in an opinion piece published in the Financial Times in early November.

Even more surprising is a statement on the website of the Dutch central bank, De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), as the Netherlands adopted the euro right from its inception 1999. In defence of its large gold holdings that has reached 612.5 tonnes, worth over 6 billion euros, the bank said in a statement on its website:

Shares, bonds and other securities are not without risk, and prices can go down. But a bar of gold retains its value, even in times of crisis. That is why central banks, including DNB, have traditionally held considerable amounts of gold. Gold is the perfect piggy bank – it’s the anchor of trust for the financial system. If the system collapses, the gold stock can serve as a basis to build it up again. Gold bolsters confidence in the stability of the central bank’s balance sheet and creates a sense of security.2

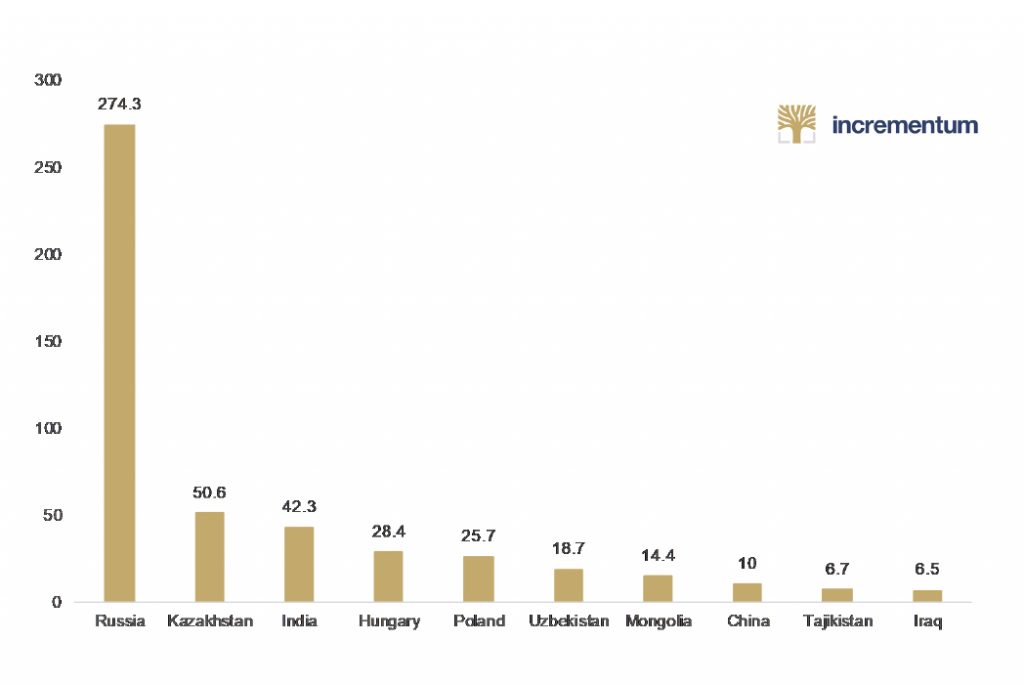

Europe is a latecomer in joining the global drive by central banks to increase gold reserves. In buying 657 tonnes of gold in 2018, central banks globally have made the largest purchases of gold since the end of Bretton Woods in 1971. Russia (274 tonnes), Kazakhstan (50 tonnes), and India (42 tonnes) were the largest buyers, while Hungary and Poland – another EU member state that has not introduced the euro and has no immediate plans to do so – rank fourth and fifth in this list. Poland made its largest purchase since 1998.

The high demand from central banks continued in the first three quarters of 2019. According to the World Gold Council, central banks increased their gold reserves by 547.5 tonnes at the end of September, 12% higher than the same period in 2018.3 It is thus quite likely that a new record will be set in 2019. These developments are in line with the results of a survey conducted by the World Gold Council: 76% of central banks consider gold as a highly relevant safe haven asset, and 59% valued gold’s effectiveness as a portfolio diversifier.4

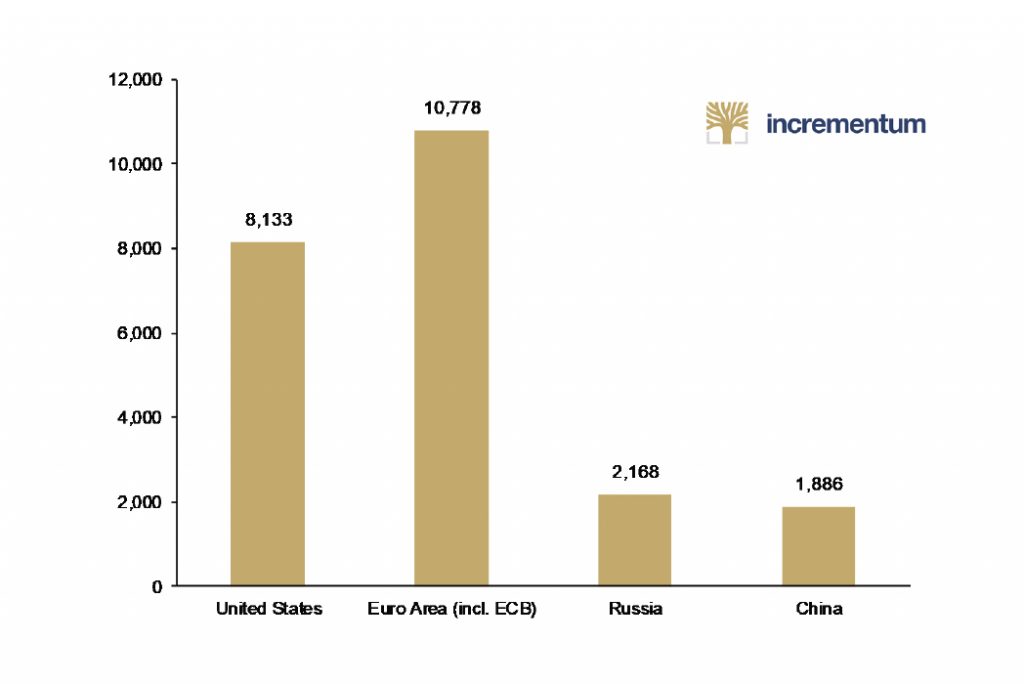

It might come as a surprise that the gold reserves of the 19 countries in the eurozone are almost one-third higher than those of the United States (US). Russia’s and China’s gold reserves trail far behind, despite both countries’ gold purchases last year, which in the case of Russia was more than five times of second place Kazakhstan.

Gold purchases (tonnes), 2018

Gold reserves (tonnes), 2018

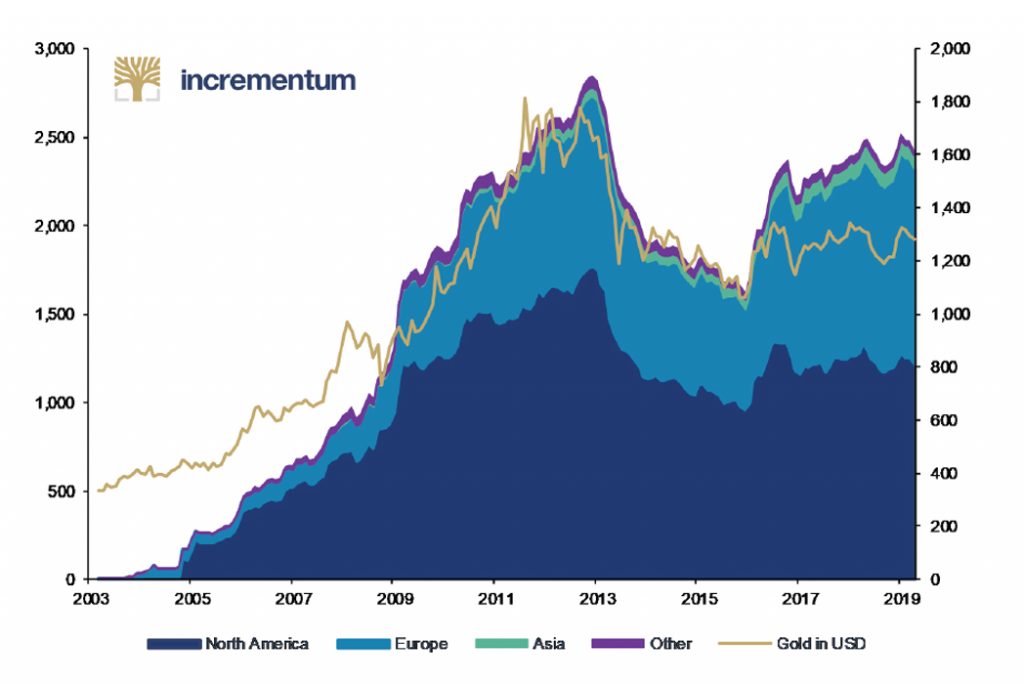

ETF gold holdings (tonnes) and gold price (US$), January 2003 to April 2019

ETFs

Interest in gold among financial investors is slowly rising again. This can be seen by the amount of inflows into gold ETFs, which have been on the rise since the end of 2015. For us, this indicator is representative of Western financial investors, who view exchangetraded funds (ETFs) as the primary instrument for managing their gold exposure. This is also reflected in the fact that gold ETF inflows follow an extremely procyclical pattern.

Geographical segmentation shows that in recent years, European investors have weighted gold ETFs more strongly than their North American peers. Since 2016, European exchange-traded products (ETPs) have increased rapidly and have reached a new record high. Assets under management in European gold ETFs rose to 1,134 tonnes at the end of 2018. This is now equivalent to 46% of the total market.5

We interpret this increase primarily as a consequence of the devastating zero or negative interest rate environment, aggressive European Central Bank (ECB) policy, smoldering fears of recession, and political developments, as well as the rather weak stock market performance in Europe, especially relative to US markets.

PRIVATE INVESTORS

Despite significant differences across Europe, private investors continue to show a strong interest in gold, according to the Edelmetall-Atlas Schweiz report published by the University of St. Gallen produced in cooperation with Philoro Schweiz.6 After real estate but still ahead of equities and fund investments, gold ranks second among the most popular forms of Swiss investment. Almost every fifth Swiss national considers it likely that he or she will buy gold in the next twelve months.

According to the report, the most important reason why investors buy gold is for long-term investment, followed by security, stability, asset accumulation, and finally returns. This shows that the typical Swiss gold investor is long-term-oriented and not focused on shortterm speculative gains. Of interest too are the results regarding the question as to where people prefer to buy gold. In all age groups, the investor’s home bank ranks first; nevertheless, there are clear differences in purchasing behavior among different age groups. The older the investor, the more often the home bank is chosen. Second among the youngest investors (18–29 years) is buying gold online, while among 30–39 year-olds, physical outlets of precious metal dealers take the second spot.

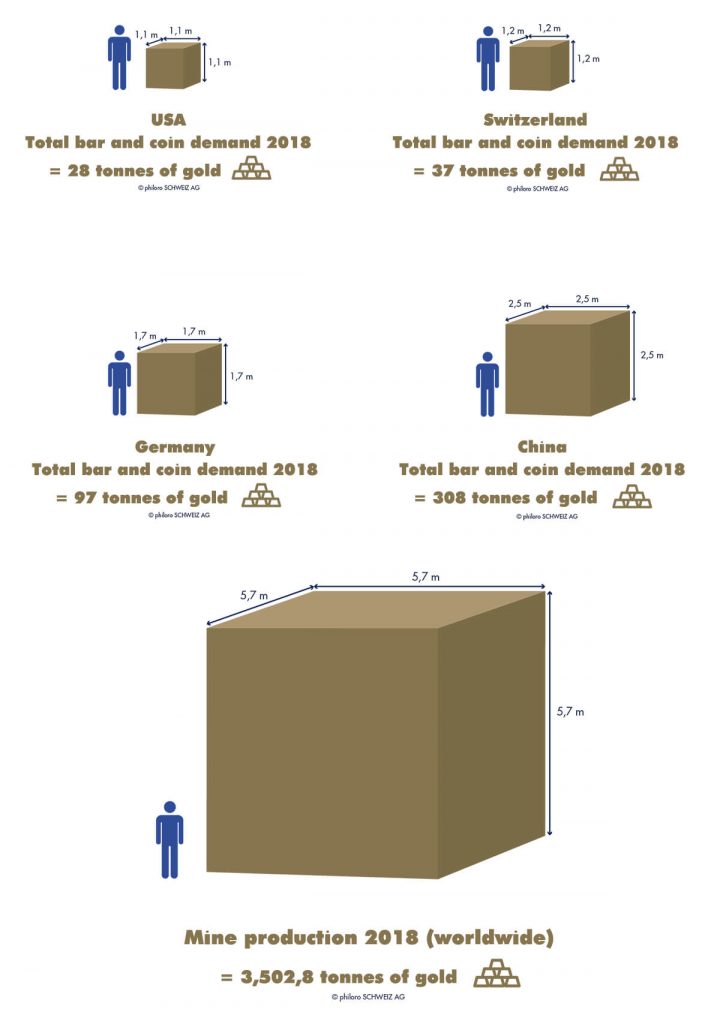

The comparatively high affinity of the Swiss for gold is summarised in the following chart. The demand for gold by private investors in Switzerland exceeds the US and on a per capita basis is significantly higher than the demand in Germany or China.

Gold demand (tonnes) and mine production (tonnes), 2018

CONCLUSION

Europe might be called the “old continent” and be struggling in various fields such as economic growth, innovation, and demography. Nevertheless, or rather because of this, interest in gold, a crisisproven asset, has increased in recent years, not only among private and institutional investors, but also among central banks. Far from being a “barbarous relic”, gold is making a strong comeback on the old continent, which seems to be only in its early stages.

Notes

RONALD STOEFERLE is managing partner of Incrementum AG, responsible for research and portfolio management. In 2007, he published his first In Gold We Trust report. Over the years, the study, which is available in English, Mandarin and German, has become one of the benchmark publications on gold, money, and inflation. He is an advisor for Tudor Gold Corp. (TUD), a significant explorer in British Columbia’s Golden Triangle, and a member of the advisory board of Affinity Metals (AFF).